“For King and Country”: The War Time History of Burrard Dry Dock, North Vancouver

Much has been made in recent years about the war effort on the home front in Canada from 1939 to 1945. Stories are now emerging about war bond fundraising efforts on the Prairies, Ontario hospitals training new nurses to specifically serve overseas and a number of “Rosie the Riveter” type recollections in the ammunitions factories all across Canada. With the 100th anniversary of the Canadian Navy having occurred in 2010, other home front stories are now getting more attention. Canadian men and women worked side by side during the war years to build naval destroyers, corvettes, and supply ships. One such place that churned out a large number of those supply ships was the Burrard Dry Dock in North Vancouver, British Columbia.

By the end of war in 1945, Canada had the fourth largest Navy in the world behind the US, Britain and Germany…a staggering accolade for a country that only had a population just over 11 million people. Prior to 1939, the area of North Vancouver around the Burrard Dry Dock was a sleepy little coastal community of just over 2,000 inhabitants and employees. Clarence Wallace was the owner and director of the Burrard Dry Dock during the war and he was carrying on a long tradition of shipbuilding that his father had started. Alfred Wallace began Wallace Shipyards at False Creek in 1894 and moved the operation to North Vancouver in 1906. Ships being built here included CPR ferries and small research vessels. One of the most famous ships to have been built in North Vancouver by Wallace Shipyards was the RCMP Arctic patrol vessel, St. Roch, in 1928. The St. Roch made history when it became the first ship in history to sail through the Northwest Passage in 1942, a feat that had been sought by mariners, explorers and world navies for centuries. If you are ever in Vancouver, try to visit the Vancouver Maritime Museum where the St. Roch is displayed. The ship has been designated as an artifact of national historic significance by Parks Canada and the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

In 1929, Alfred’s son Clarence took over the business but there was little activity in terms of shipbuilding in BC during the interwar years. The Burrard Dry Dock’s competition, North Vancouver Ship Repairs, did virtually that, just repairs and Wallace’s company did much the same. At the time, Britain was reluctant to help fund, support or send technical consultants to colonial shipyards for fear that these distant companies would rise up to become competitors with the mighty English and Scottish shipbuilding industry. However, when France capitulated to Germany in 1940, Britain soon stood back and realized how vulnerable they were to invasion and called upon countries like Canada and the US to help build ships that would send supplies to the war front in Europe. Thus, Wallace turned his little dockyard into one of the most productive in Canada.

Clarence Wallace was no stranger to the hardships of war. He fought with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the Great War and was severely gassed during the Battle of Ypres. He nearly didn’t survive, but made a strong willed and miraculous recovery and was awarded a medal for his bravery. He also lost a son in the Second World War so he understood full well the hardship of war loss and injury in ways most people didn’t. This experience, and his dedication to production, contributed to his company’s success. The Wallace Shipyard Company was renamed the Burrard Dry Dock just before the start of the war and it quickly became the largest employer of shipbuilding on the BC South Coast.

The Battle of the Atlantic from 1940 to 1943 was a very risky and often deadly enterprise for the merchant navy as well as the convoys of Canadian Navy supply ships heading to Europe. German U-Boat fleets hunted Allied ships in groups called “wolf packs”. Their hunting tactics resembled wolves as the U-Boats would surround a convoy in a tight circle, trapping the group before open firing with torpedoes. The loss of life and supplies was an enormous blow to the Allies in the early part of the war and it had men like Mackenzie King, Sir Winston Churchill, and Franklin Roosevelt very concerned about the Allies chance of winning the war. While some items like Canadian built Lancaster bombers could actually fly across the Atlantic to their new squadron homes in places like Yorkshire, East Anglia, or North Africa, other items needed sea transport to get to Europe and Canada played a very vital role in getting these desperately needed supplies across the Atlantic.

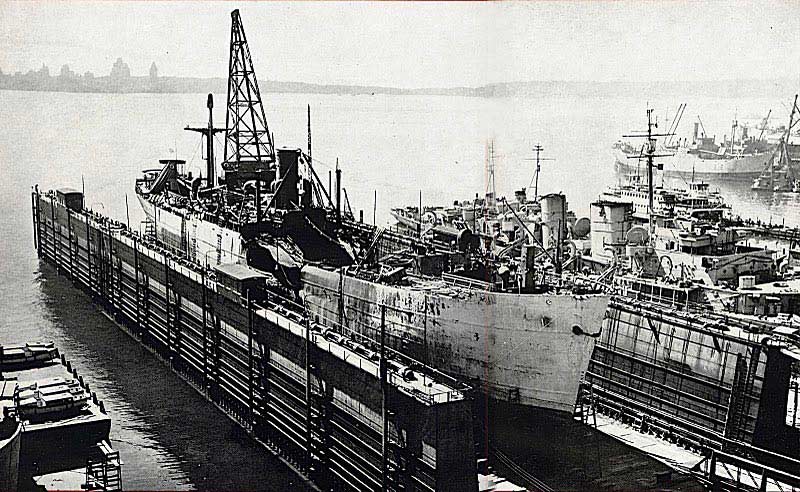

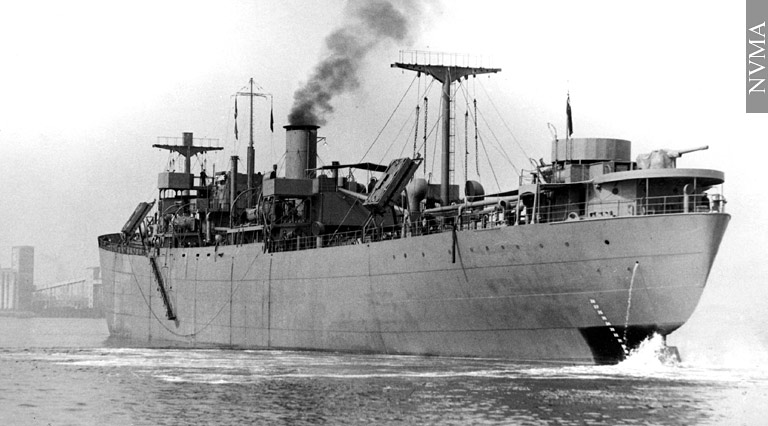

Canadian Navy cargo ships were built strictly for function and not comfort or style. Each ship was able to hold 6,270 tons of bacon, ham, cheese, flour and canned goods to be sent to troops overseas, 2,150 tons (1,950 t) of steel bars and slabs; enough Bren-gun carriers, tanks and motorcycles to equip an infantry battalion, 1,900 tons (1,723 t) of aircraft bombs, 2500 tons of machine gun bullets, enough lumber and nails for 90 four-room cottages; two complete bombers which would be assembled in England, and the aluminum required to build 310 medium bomber aircraft. In accordance with the DEMS (Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships) plan, the vessels were armed with anti-torpedo nets, rifles, machine guns and anti-aircraft weapons. A crew of 50 men would take the voyage and half the these men were Canadian defense personnel specifically trained to operate the guns and anti-submarine equipment. These ships were some of the best equipped cargo and merchant ships on the Atlantic in terms of their weaponry. In all, Canada built 354 supply ships which were built specifically to replace the ones lost by the German wolf packs. Clarence Wallace’s quota was only to produce a quarter of the ships needed but he promised that he would increase this output by 50%. The Canadian Navy was sceptical, so was the Merchant Navy. In the end, Wallace’s Burrard Dry Dock produced just under half of the 354 ships built, making it the most productive shipyard of the Canadian cargo shipbuilding industry.

Part of the reason for Wallace’s success was he had three shifts working around the clock non-stop from 1941 to 1944. The mild, temperate climate on the South Coast of BC also had an impact on the amount of time shipbuilders could work. Major snowstorms or hurricane force storms in Halifax, which battered the shipbuilding industry periodically during the war, slowed production down. But these events were never an issue for the shipyards of North Vancouver.

From 1942 to early 1944, 14,000 people worked at Burrard Dry Dock over the three shifts. Of those 14,000, nearly 1,000 were women. These workers came from all over British Columbia and even as far away as Regina to find work. Hundreds of others still were employed to build small cabins to house the influx of workers. Entire neighbourhoods sprang up in North Vancouver. Many of these homes have now been torn down and replaced with modern housing or commercial space. One of the biggest shipworkers settlements in North Vancouver was torn down to make way for the Capilano Mall in 1967. At the end of each eight hour shift, a whistle would sound and workers would make their way out to the front entrance where foot ferries would take some workers to downtown Vancouver and Street cars were lined up outside the Dock to take other workers up the hill to the North Shore communities. In those days, there were no regulations as to how many could crowd into a ferry or street car. When the interiors were full, workers would hang off the sides and cling for dear life so they wouldn’t be dumped into the middle of Burrard Inlet!

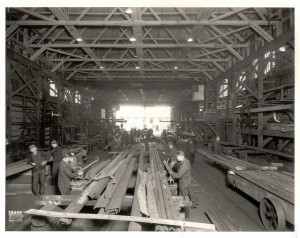

These cargo ships were built from the bottom up and put together like a giant jig-saw puzzle, following a specific, single pattern design. In total, from start to finish, it took about 100 days to build a cargo ship. First, the keel was laid and the bottom finished. The plate shops cut out the sections that were needed. Then, these plates were transported down to the assembly area to be fastened together, piece by piece, according to the design. Huge cranes swung each plate into position and they were riveted together using red-hot steel pins. This was the old method of fastening ships together and was a very different technique to what the Americans were doing. They were using the brand new technology of welding plates together, but Wallace felt the old method of riveting was more reliable. He argued that the technique of welding was so brand new that he was not willing to risk the possibility that the hulls and plates may blow apart, causing the ship to sink in the Atlantic. When I was last in Liverpool checking out the UNESCO World Heritage site, I came across a demonstration of the old method of riveting. The methodical pounding of pin against steel by one demonstrator was very loud and could be heard hundreds of yards away down the pier. I can only imagine the sound of hundreds of men and women from the Burrard Dry Dock shipyard doing the same thing 24 hours a day for nearly 4 years! I wish I could go back in time just to see how that would have sounded from either downtown Vancouver or the top of the North Shore. I think it makes sense that Wallace stuck with the old tried and true riveting methods as it was more familiar to trained shipbuilders at the time and because getting these ships out to sea was so crucial to the war effort, he didn’t want to spend valuable time on retraining those workers on the new welding technology. Besides, no one at the time knew how the welding would stand up to salt water. Each ship’s hull needed about 383,000 rivets to hold it together. Holes were predrilled in the steel plates, which were aligned with bolts and finally riveted together. This job was very labour intensive but the technology was tried and true. I’m sure Wallace was happy with his decision as history would later reveal that the American Liberty ships, that were fully welded, later came apart at the seams and had sunk under their out weight without help from either Japan or Germany.

In terms of employment, it was a great time to be a woman in the 1940s. Women were paid the same wages as men, received the same training in riveting, electrical work and steel cutting and earned the same medical and housing benefits. But, at the end of the war, all women working in the Burrard Dry Dock’s assembly ranks were forced to give up their jobs to the men returning from war. The women could stay on, but only if they accepted the scarce clerical, receptionist, or cafeteria positions. The unions tried to intervene on their behalf, but it was to no avail. Not only Wallace, but other leaders of prominent businesses across the country argued that it was impossible to expect them to maintain separate women’s facilities such as washrooms or change rooms as so many men were returning from the war seeking work. Women who chose to remain in traditional men’s job where they could, faced public criticism from both men and women, that they were taking work away from an able bodied man.

By 1943, the German Navy began turning their wolf packs away from the Atlantic as the Allies had increased both their naval and airpower in the region. The RAF’s Coastal Command send planes out specifically to guard convoys and bomb German U-Boats, while Canadian built corvettes, destroyers and mine sweepers found increasing success in staving off German attacks on the convoys. As a result, the demand for supply ships began to decrease and there was no longer any need to produce a ship every 100 days. After the war, the Burrard Dry Dock continued on, but at a much slower pace and the focus turned to building ferries and repairing existing ships. For his efforts and impressive contributions to the Canadian war effort, Wallace was made a Commander of the British Empire, two steps below a knighthood. In 1950, Wallace served as the province’s first BC born Lieutenant-Governor, a post he held for five years. In 1972, Wallace sold the shipyard to Canadian Forest Product’s Cornat Industries and the company was renamed Burrard-Yarrows Shipyard. Clarence Wallace passed away in 1982 and the company was sold again in 1985, becoming Versatile Pacific Shipyards. During the 1970s and 1980s, the shipyard produced a number of BC ferries and a number of notable ships, including the Canadian ice breaker, Terry Fox. With a large number of shipyards now dotting the BC coast since the war years, Versatile felt it was no longer competitive enough to remain open for business and shut down operations in 1994.

The buildings lay derelict for many years until 2006 when the City of North Vancouver began looking at the possibility of revitalizing the waterfront along the Lonsdale Quay area. Plans were drafted up to build a new, state-of-the-art Maritime Museum of the Pacific and to possibly restore or rebuild the dry dock buildings to house interpretive displays, shops, restaurants and other tourist friendly attractions. The site will also have an extensive commemoration site dedicated to the history of North Vancouver’s shipbuilding industry. The site has been designated as one of primary historic site significance by the City of North Vancouver’s heritage inventory.

Before the onset of World War II, the Canadian shipbuilding industry on the BC South Coast was primitive compared to the vast technological advances seen in the Clyde shipyards of Scotland. Only small vessels like the tiny St. Roch were being built along the Burrard Inlet before Wallace turned the Burrard Dry Dock into a bustling and highly productive operation. The history of Burrard Dry Dock is another story about the inspiring Canadian war effort on the home front and how quickly a small population came together in many important ways to not only win the war, but help build thriving communities that exists today such as North Vancouver, nestled beneath the North Shore mountains of British Columbia.

A special thanks to the North Vancouver Museum Association for the photos as well as the information for this story.

No Comments to ““For King and Country”: The War Time History of Burrard Dry Dock, North Vancouver”