The Great Toronto Fire of 1904

Although the date of April 19, 1904 would suggest it must have been a very pleasant and mild spring day in Toronto, it was actually quite the opposite. The temperature was -4 Celsius and there were flurries in the air that evening in the downtown core. But the winter-like conditions were the least of Toronto’s worries. People were furiously jumping off the streets and onto the sidewalks to avoid the charging horse teams that pulled 7,500 pound fire engines down Wellington Street West at about 8:30 that evening. When the night was over, Toronto had lived through the worst city fire in its history.

Fire is just one of those unavoidable things that nearly every city and town in every nation the world over has experienced. From Rome in 64, London in 1666, Montreal in 1734, Chicago in 1871, Vancouver in 1886 just to name a few, so many cities have either been completely levelled or have had several blocks destroyed. The Great Toronto Fire of April 19, 1904 is one of those fires.

The fire of 1904 was not the first or last fire in Toronto’s history, but it was the worst in terms of businesses lost and lives affected. The first major fire to occur in Toronto was the Great Fire of 1849. Back then, the population of Toronto was only about 25,000 and this fire was particularly devastating because the majority of the buildings were wooden. The aftermath of the 1849 fire saw a number changes in the city’s building codes. Wood constructed buildings in the downtown core were banned and all buildings had to have a brick firewall separating each structure. Fire hydrants, which were introduced to the city in 1842, also increased in numbers to help battle future blazes. This was done partly because one of the buildings to have been destroyed belonged to the Water Company. This meant fire fighters and citizens had to drag buckets of water up from Lake Ontario to douse the flames.

We’ll never know for sure what caused the fire in 1904 though some theories have been speculated. Some have argued faulty wiring or possibly a stove was left on in one of the businesses. Another theory suggests a hot iron was left plugged in beside a pile of cotton rag materials. We do know that the fire was spotted just after 8pm by a Toronto city constable walking his regular beat that night. He noticed flames shooting out of the elevator shaft at the E&S Currie Neckwear Company building at 58 Wellington Street West. He immediately raised the alarm but the fire was spreading fast and furiously. By 9pm, every single available fireman in Toronto was called in to battle the blaze. By 10pm, the fire had now spread to both sides of Wellington and up to Bay Street. The City’s Mayor, Thomas Urquart, responded to Fire Chief John Thompson’s request for as much help as possible. Urquart sent out urgent telegrams for assistance to nearby communities and by 11pm, fire fighters were rushing in on special express trains from as far away as Hamilton, St. Catharine’s and even Buffalo, New York. Shortly after his request for assistance had been sent, Urquart learned that the fire had now spread to Front Street and was heading south to Esplanade and east to Yonge Street. It seemed like an unstoppable inferno and the fire fighters were growing exhausted. The extra help did arrive in time to help douse the flames and by 4:30am, the fire was declared under control.

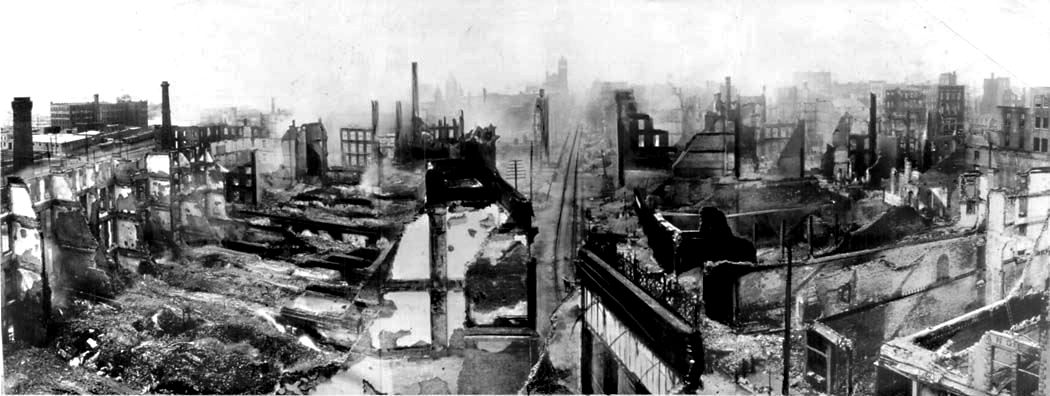

There were a number of factors that caused difficulty for the fire fighters to contain this fire and prevent the rapid spread. If you look at the picture immediately above of the ruins along Front Street, you will notice all kinds of power and telegraph wires. These wires made it extremely difficult for fire fighters to get their ladders through in order to get on top of the fire to stop the advancement. All major cities were a myriad of wires, cables, poles and junction boxes and many of these wires were much lower to the ground than they are today. These wires could not be safely cut at the time, so fire fighters had to do their best to try to get around them. Another factor was the low pressure water system in place. Even though most of the horse drawn fire pumps were steam powered, it still took a great deal of physical strength to be able to continuously pump water out. For this reason, to reach the upper floors of the buildings, ladders were essential. High pressure pumps would finally be brought to Toronto in 1906 and the first motorised fire truck was purchased by the city in 1911. A third factor in the quick spread of this fire was due to the design of the buildings themselves. Though many of the buildings had stone or brick outer facings, many interiors were still made of wood such as stairwells and open elevator shafts. The open concept of these features provided the perfect opportunity for fires to spread quickly from one building to the next. Also, this fire took place in a manufacturing section of the city. This meant that open spaces under stairwells, in service elevators and large storerooms held hundreds, if not thousands, of boxes of manufacturing supplies from paper, fabrics, solvents, and other highly flammable products. The products simply helped to fuel the spread of the fire.

In the above picture, you can see from this City of Toronto Fire Insurance Map the extent of the fire. In all, 122 buildings were destroyed, either by fire or severe water damage, putting about 5,000 people out of work. Miraculously, there were no deaths in the fire. Because it was in a manufacturing section of the city, the workers had gone home for the day. There were a few serious injuries reported, however, mainly to fire fighters including Fire Chief Thompson who broke his leg in a fall.

Some of the unemployed workers went down to help clear the debris in the days and weeks following the fire. Many businesses were able to find new locations to restart their operations. Some, unfortunately, were never able to recover their losses and were forced to close permanently. The smouldering ruins cast an eerie glow over the city as the following pictures reveal.

Within days, the remains of the buildings were brought down with controlled dynamite blasts to prevent them from toppling down on the cleanup crews in the streets. On April 21, 1904, the City of Toronto’s Architect, Robert McCallum urged city officials to take this fire very seriously and implement measures that would cap buildings to a maximum height of seven storeys. He argued that limiting the height of buildings would aide fire fighters in controlling future fires. We now know, in hindsight, that McCallum’s request was ignored. One of his requests that was taken seriously, however, was his suggestion to change some building practices in the city. Stairwells and elevator shafts would now be closed off to help contain future fires. Only three of the buildings involved in the fire had sprinklers systems. New building codes now made sprinkler systems mandatory in all buildings higher than three storeys. With these mandatory sprinklers and, of course, with the introduction of high pressure water pumps to Toronto in 1906, architects now felt they could construct buildings of unlimited height.

Many of the buildings that were destroyed were relatively new. Many had been there less than twenty years while some were less than two years old. These buildings were deemed very modern for the time in terms of construction, design and amenities. Once the rubble was cleared away, businesses worked on constructing new buildings as quickly as they could. Would Toronto look any different today down Bay, Wellington, Front, Esplanade and Melinda Streets had the fire not occurred? Could some of those buildings still be there today? It’s hard to answer that question. Most cities around North America experienced widespread demolition of their heritage structures from the 1950s to the 1970s so it is possible they would have been torn down anyway. And judging from the modern office buildings that now line those sections of Bay, Front and Wellington Streets it’s very difficult to guess whether these older buildings that pre-dated the fire would have been retained in some way.

A special thanks goes out to the City of Toronto’s Archives, the Toronto Public Library and the Archives of Ontario for the information to produce this story.

No Comments to “The Great Toronto Fire of 1904”