The Story of the Real ‘Winnie the Bear’

The Canadian Expeditionary Force in WWI was no stranger to regimental mascots and pets. Lt. Col John McCrae had two of them and it is said that there were at least two regiments that had bears as mascots and one even had a beaver! Yet, the most famous Canadian mascot of all from 1914-1918 was a little black bear from White River, Ontario that would inspire a British author to create a character that is known around the world today to millions of children.

When most hear the name Winnie the Pooh, we immediately see a lively, golden coloured teddy bear wearing a red shirt, constantly losing his eyes and madly clutching his blue “hunny” pot. But the real Winnie the Bear, was much different in appearance. British author A. A. Milne would take his son Christopher Robin to the London Zoo almost weekly in the early 1920s. Christopher Robin’s favourite animal at the zoo, by far, was a black female bear named Winnie, who had been donated to the Zoo by a Canadian Army veterinarian. This bear was so friendly and tame, that Christopher Robin could feed her spoonfuls of honey without any fear. He was so taken with Winnie that he named his own teddy bear after her. But what was the story of this little bear? She was not the only bear at the Zoo, but she was an obvious stranger in a country that had no black bears of its own. Where did she come from and how did she end up at the London Zoo? The answer to that starts back in Birmingham, England in 1887.

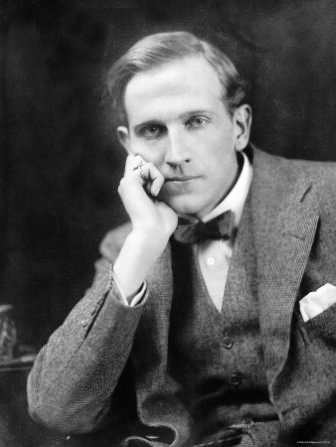

Harold (Harry) Colebourn was born April 12, 1887 in the heart of Birmingham, England to a working class family. Harry showed a gift for math and sciences growing up and had his heart set on becoming a veterinarian based on his deep affection for all animals. But the young Harry also had an adventurous side and yearned to stretch those wings. He had known families in the Birmingham area who had relocated to various parts of Canada, including the Prairies. Looking for a way out of the factory city he grew up in, Colebourn took the bold step to come to Canada alone just after his 18th birthday in 1905 to pursue his dream of becoming a veterinarian. He first came to Toronto and spent the next three years struggling to sell fruit door to door and working as a deck hand at the Toronto harbour, to earn enough money to go to school. In 1908, he enrolled in the Ontario Veterinary College in Guelph, Ontario and on April 25, 1911, Colebourn graduated with full honours and a degree in veterinary surgery. After graduation, he returned to England to spend a few weeks with his family before receiving a letter he had been waiting for. He had been offered a job with the Department of Agriculture’s Health of Animals Branch in Winnipeg, Manitoba and they wanted him to start in July of that year. So after just a few short weeks, Colebourn left England again to travel west to his new home of Winnipeg.

Shortly after Colebourn arrived in Winnipeg to start his position, he joined the 18th Mounted Rifles and was transferred to the 34th Regiment of Calvary, which later changed its name to the 34th Fort Garry Horse. When war broke out in 1914, Colebourn immediately offered to volunteer and was enlisted to be a veterinarian with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. He was instructed to make his way to Valcartier, Quebec, which at the time was the largest military training camp in the British Empire, to begin his basic training before being sent to southern England for further training. His train departed Winnipeg on August 23, 1914. The next day, the train made a scheduled stop in White River in northern Ontario to bring on new passengers as well as cargo. White River was half way between Winnipeg and Toronto and a natural place to stop for a few hours. Colebourn stepped off the train, like a great many of the passengers, to stretch his legs. On the platform, something caught his attention.

There was a trapper near the end of the platform with a tiny black bear cub on a leash. The man was trying to sell this bear cub but people kept walking past seemingly ignoring his solicitations. Colebourn watched for a few minutes as people walked past. Soon, his own curiosity was too great and he walked up to the trapper to ask about the little bear. The trapper told Colebourn he had shot the bear’s mother. He didn’t realise this bear had a cub until it came wandering out of the bush looking for its mother. The trapper said the cub was a female and refused to leave his side. He felt he could come to the train station and maybe someone could buy her and raise her as a pet. Colebourn looked down at the very quiet and well behaved cub and asked “How much?” The trapper answered “Twenty dollars do it?” Colebourn pulled out his wallet and looked through what he had. He hesitated for a moment, looking at the bear before he finally said “yes, twenty dollars will do it.” Colebourn paid the trapper then picked up the little cub and carried her around like a puppy, forming a bond with her, for the next hour before the train departed.

For the next couple of days on his way to Valcartier, via Toronto, Colebourn formed a strong bond with his bear and named her Winnipeg, which later got shortened to Winnie. He would exercise Winnie by walking up her and down the train car aisles. Winnie would dutifully follow behind, stopped when he stopped, and licked the hands of all the passengers who would reach over to pet her as she went past. Colebourn arrived at Valcartier where Winnie became the official mascot of the Second Canadian Infantry Brigade and was a much beloved pet to everyone. But Colebourn was clearly Winnie’s favourite as she would try to follow him everywhere he went and if she was forced to stay behind, she would cry like a child. On October 3rd, 1914, Colebourn and his regiment left Canada for the Salisbury Plains in southern England. Here, all Canadian regiments would receive additional training before being sent to France. Over the next couple of months, Winnie kept growing in physical size and in the hearts of the Canadian men. Sadly, in early December 1914, Colebourn was given the order to abandon Winnie. She would not be travelling to France with the regiment due to her size and the fact that her presence in the trenches might be a danger to herself and others. On December 9th, Colebourn took Winnie to the London Zoo where she was put on loan. He had every intention at the time of reclaiming Winnie and taking her back with him to Winnipeg at the end of the war. He made the Zoo staff assure him that Winnie would be cared for, fed properly, and placed in a decent sized enclosure to allow her freedom of movement. Colebourn had been assured these would happen and he sadly left Winnie behind while he went on to France.

Over the next few years, Colebourn was able to come back to London, while on leave from his duties, to visit Winnie. She always recognised him and would get excited when he approached the enclosure. The London Zoo staff said that Winnie was the most popular animal at the Zoo and she had earned a reputation with her keepers as the most tame and gentle bear the Zoo had ever had. She was particularly popular with children who would feed her spoonfuls of honey inside the cage with the keepers present. Seeing how happy Winnie was, how well cared for and how popular she had become with guests, Colebourn decided to renege his “on loan” offer and outright donated her to the Zoo. In 1919, a dedication ceremony was held at the Zoo in which hundreds, including Colebourn and some of his regiment, attended. Colebourn stayed on in England for another year taking further veterinary training and said a final goodbye to Winnie in 1920 before returning to Winnipeg.

In the mid 1920’s, British author Alan Alexander Milne began bringing his infant son, Christopher Robin, to the London Zoo. Little Christopher Robin was so taken with Winnie that he named his own teddy bear after her and begged his father to write a story about Winnie. What A. A. Milne wrote in 1926, would become one of the most popular series of childrens’ books of the twentieth century, which outlined the adventures of Winnie the Pooh, Christopher Robin, Piglet, Tigger and all their friends.

As for Harry Colebourn, he set up a private veterinary practice in Winnipeg, married and had a family. His health had never been perfect all his life and the long hours of running a private practice took a toll on him physically. He was forced to abandon the practice in 1926 and went back to work for the Department of Agriculture’s Health of Animals branch. He was able to manage some private work on the side, but not to the extent of being able to run it full time again. Colebourn retired in 1945 and passed away September 24, 1947 at the age of 60. Because of his war veteran status, he was buried in Winnipeg with a military stone to mark his grave.

Winnie went on to a long life after the war. She continued to be a major attraction for the Zoo and she died at the age of 20 in 1934, a remarkably long life for a bear in captivity. A memorial service was held in which hundreds came, including A. A. Milne. In the early 1980′s, a statue dedicated to Winnie was erected in the London Zoo near her old pen.

The little black bear cub from White River, Ontario who loved people, and honey, would go on to inspire the love and admiration of one author who, in turn, inspired others with his children’s books.

This story was presented in a pretty decent 2004 movie, A Bear Called Winnie. It’s worth a look if you can find it on DVD.

Hello David,

Thanks very much for your comment. Yes, I have actually heard of this film but haven’t been able to find a copy so far. The BBC also did a nice little one hour special a few years back that combined documentary style reporting and dramatic re-enactments which I saw over there recently. It’s nice to see how Harry Colebourn and his little Winnie are still remembered fondly in the UK.

Thanks for reading!

Cheers,

Laura

Hi Laurie,

Great story on Winnie! It’s one of those great bear stories right up there with Paddington Bear. I had both as a kid. It’s no secret my Mum wanted a girl! LOL! Thanks for this. I had heard bits and pieces of the story, but you filled in all the holes I didn’t know before.

Best,

Mark

Hi Mark,

Glad you liked it. I admit, I was more a Paddington fan myself. I blame my British grandmother for that! I still treasure that Paddington I bought in Leeds!

Cheers,

Laurie