Portrait of a Nation: The Photographs of William Notman and Son Studio, Montréal

The nineteenth century was a pioneering time on so many levels for Canadian society. It was a great century for the expansion of the west, the Confederation of the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada and scientific discoveries led to the development of the telegraph, electric power and the automobile by the end of the century. Yet, in these developments, there was also a revolution happening in the heart of Canada’s cultural and artistic mecca of Montréal. That revolution, which would transform Canadian society from coast to coast, was the development of photography. Throughout the nineteenth century, and well into the twentieth, an image of Canada was broadcast to the rest of the world as a place of beauty, grandeur and vast diversity in its landscapes and its people. At the forefront of that revolution of photographic wonder was the William Notman and Son Studio from Montréal.

1826 was a ground breaking year for photography. That year, France’s Joseph Nicéphore Niépce created the world’s first photograph by reflecting an image of a wall located on his country estate against a silver plate which was then coated with bitumen solvent and given time to dry. When the solvent had dried, the plate was washed with lavender oil to remove the excess bitumen leaving a permanent image in its place. The exposure time needed to dry the bitumen took upwards of eight hours, so it was an impractical process to use for portrait photography. Between 1830 and 1850, several improvements were made in photography. Most notable among the inventors were Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, who created the daguerreotype suitable for portraits, and William Fox Talbot who created the calotype process which allowed exposure times to be greatly reduced over previous inventions. Talbot’s invention was considered to be the most user-friendly process at the time and amateur photographers right across Britain could buy a licence, worth four pounds a year, to experiment with their own ideas. One young man who bought a Talbot licence was William Notman.

William Notman was born March 8, 1826, the same year Niépce produced the world’s first photograph. He was born in Paisley, a small community several miles west of Glasgow, Scotland. His family were dry goods merchants and haberdashers and he was expected to follow that path as well. However, Notman’s passion was photography and he experimented with a number of development techniques as well as different subjects. In 1855, a great depression was sweeping through Scotland and Notman found himself teetering on the brink of bankruptcy with the family business. He tried to “cook the books” in a desperate bid to keep the business going for as long as he could to weather the economic downturn. With his luck running out, the business eventually failed and the law had caught on to his elaborate accounting scheme. Faced with the very real threat of being sent to debtor’s prison, Notman knew his only way to avoid this fate was to flee Britain. In the summer of 1856, William Notman arrived in Montréal to look for work and find a residence so that he could eventually bring out his wife and daughter. He briefly worked for John Ogilvy who operated a dry goods business in downtown Montréal. But William Notman had bigger dreams in mind.

It was no wonder that Notman felt at home in Montréal. From 1800 to 1850, the city’s population rose from 9,000 to 50,000 people. The group leading the way in immigration to the city were the Scots. Although the Scottish made up a small portion of Quebec’s overall population, they would play a major role in the development of the arts, commercialism, banking, universities and railroad development in Montréal. And in those influential people, Notman saw a business opportunity. In December 1856, with his wife and daughter now in Canada, Notman embarked on his lifelong dream. He opened the William Notman Studio in a tiny room on Bleury Street and it was one of the very first photograph studios anywhere in Canada, let alone Montréal.

For the first two years, Notman worked alone. He took portraits of the city’s elite merchants, bankers, politicians, militiamen and other enterprise leaders plus their families. In those first two years, Notman could not afford elaborate backdrops or furniture, so his early portraits are quite plain in appearance. But this didn’t matter. Notman had a unique ability to capture the very essence and soul of his subject in that brief moment in their lives. Even these early photographs capture a sense of wonder and excitement of wanting to know who these individuals were in their everyday lives. In 1858, Notman’s reputation among Montreal’s elite class for his solid photography skills earned him a lucrative contract with the Grant Trunk Railway to document the construction of the Victoria Rail Bridge across the St. Lawrence. Although portrait photography would always remain Notman’s bread – and – butter business, he would take advantage of landscape photography when the opportunity to make money from it presented itself.

Between 1858 and 1860, William Notman and an assistant worked in all weather and atmospheric conditions to systematically record the bridge’s construction. At the time, the bridge was considered a major feat of engineering in Canada and the Grand Trunk Railway wanted to have a photographic record where images could be bought as keepsakes by the public. When the Victoria Bridge was officially opened by the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) in August 1860, William Notman presented him with an elaborately carved maple box containing the full set of photographs of the project bound together in a large, leather book. It was a gift to take back for Queen Victoria, who herself was an avid amateur photographer. Notman family folklore indicates that the Queen was so impressed with the gift that she named Notman Canada’s “Photographer to the Queen”. It was a very high honour indeed for a pioneer of the photographic industry in Canada. The honour also meant that Notman would become the first Canadian photographer to reach international status.

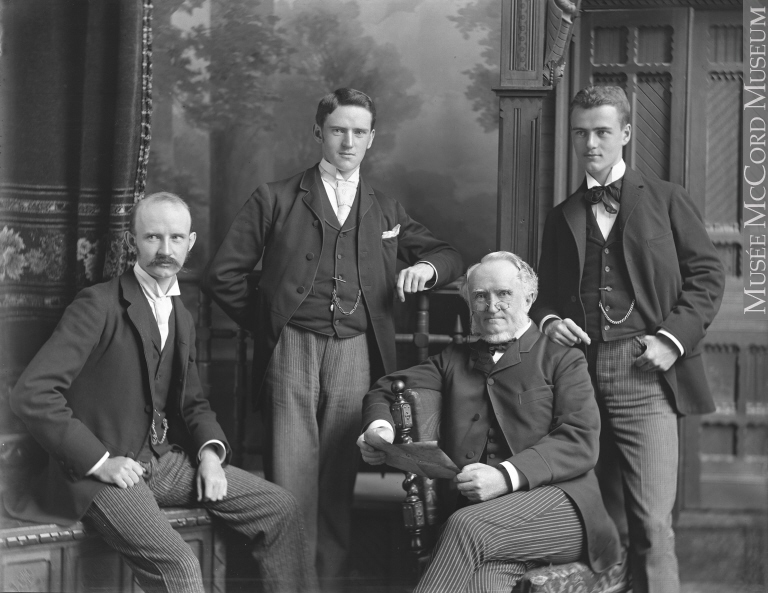

As a result of this gesture awarded by the Queen, Notman made swift use of the title. By the end of 1860, his Bleury Street shop had the title firmly carved into the portico above the doorway and he began using it in his advertisements and business stationery. Taking advantage of this new status certainly helped his business interests. Notman suddenly found himself with fifteen employees by the end of 1862 and he moved his office next door to a larger space to accommodate the increased demand for his portraits. He also began attracting the elite classes from Toronto, Québec City, Ottawa, Philadelphia and Boston. Even wealthy British aristocrats had their portraits taken as they visited Canada on business or pleasure. Word spread fast about Notman’s talents and when it came time to photograph a group of individuals who would have a profound impact on the future of Canada, only William Notman was considered for the job.

Beginning in 1863, a group of Ottawa politicians started having their portraits taken to commemorate the genesis of a political movement that would shape the future of Canada. They were the Fathers of Confederation and each came through William Notman’s door over the next several years to pose for him. At the time of these early photographs, most of these men were still only known in their own regions and wards. In each of them, Notman succeeded in capturing not just their steely political determination to protect their very young English and French cultures from American expansionism, but he also managed to capture each man as an individual. From the roguish yet thoughtful smile and unkempt attire of Sir John A. Macdonald to the passionate and stately, almost regal, appearance of George-Étienne Cartier, Notman was able to capture facets of their personalities in just one brief instant, frozen in time. One could look at these portraits and feel they knew the person they were looking at.

By 1868, William Notman was not satisfied with just one studio. He wanted to expand beyond Montréal and even beyond his province. He opened a second studio in Montréal that primarily catered to thematic portraitures which were gaining in popularity among those who could afford it. In these studio images, Notman recreated scenes in life as if they were happening in exotic locations. Hunting parties, winter scenes, soirées, wedding parties, beach scenes and anything else the client could conjure up was reproduced in studio to commemorate an event or past-time deemed important to the clients. The portraits now are an impressive historical record and often insightful look into the private lives and social activities of nineteenth century Canadians.

With his popularity among federal and provincial politicians growing, Notman opened a studio on Ottawa’s Wellington Street in 1868 as well as in Toronto. By 1872, Notman had expanded into Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the campuses of Yale and Harvard Universities to cater to the student trade. By 1877, the business had fifty-five employees and in 1882, the business changed its name to William Notman and Son when his eldest son, William McFarlane, became a full partner. At the studio’s height in 1880, William Notman had fifteen studios in Canada and nineteen studios in the United States. No other nineteenth century Canadian photographer had as much coverage, or respect, as what William Notman had achieved.

As for the next generation of Notmans, William McFarlane Notman did something that no other Canadian child had done before him: he grew up on camera. Every aspect of his life from infancy to adulthood had been captured on film by his father. Today’s families, with easy access to IPhones and digital cameras, don’t think twice about the ease of documenting their children’s lives. But William McFarlane had grown up in that golden age of the new photographic technology which made his father so famous. Yet, studio portraits were not what fuelled William McFarlane’s imagination. He considered himself a landscape photographer. So when the Canadian Pacific Railway asked his father in 1884 to document the people and landscapes along their railway in the Canadian West, William McFarlane jumped at the opportunity to get out of the studio. For the CPR, the photographs would be a means by which to sell their brand to the rest of the world through an elaborate public relations and marketing program. The CPR’s branding was to sell to the world the idea that they were responsible for opening the Canadian West to settlement and economic expansion. They wanted to project an image that they were creating a kind of playground for those seeking opportunities in the west. For William McFarlane Notman, this commission was a means to showcase the development of a young nation to the rest of the world through photographing its people and pristine wilderness landscapes.

From 1884 to 1899, William McFarlane Notman made nine trips to photograph the Canadian West for the CPR. He was given his own railcar equipped with a darkroom and all the cameras and film he would need for the project. In those fifteen years, William McFarlane captured an image of Canada that his father never achieved. He captured images of growing communities along the railway, the native peoples of the Prairies, Chinese railway labourers in the mountains of British Columbia, wealthy businessmen looking to make new fortunes in the cities of Vancouver and New Westminster and he captured images of a pristine wilderness still untouched by urban development and industry. William McFarlane’s images were sold around the world in large numbers and these images would solidify his reputation as an artist rendering a grand and exotic interpretation of a growing young nation.

In the photographs above, Kamloops is shown as a developing pioneer town on the edge of Lake Kamloops. Within a few short years, this region stretching into the Okanagan Valley would develop a vineyard and fruit crop industry that would become second only to the Niagara Region in Canada. Roger’s Pass was the highest point along the CPR line and it would become the second highest point along the Trans Canada Highway when it was paved in 1963.

William McFarlane also left us a record of not only a nation that was expanding, but of another nation that was on the decline. The photograph of the Blackfoot brave with his pony on the Plains outside Calgary evokes an image of sadness and of longing. By the turn of the twentieth century, most First Nations groups had been made to adapt to the European way of life or they had been forced onto reservations and their children sent to government run residential schools. What William McFarlane captured was the final lifestyle stages of a nomadic people who had hunted and lived off the land for thousands of years.

To give a perspective on how the physical Canadian landscape has changed from the time William McFarlane had recording his images, the next set of photos shows the Vancouver harbour front. The first picture depicts Vancouver in 1887 looking from the northwest toward the newly constructed CPR pier along Burrard Inlet. This very site would become the future home of Canada Place. The second photo shows a recent view of the Vancouver skyline from the middle of Burrard Inlet looking toward the same spot with the white sails of Canada Place in the middle of the frame.

William Notman had worked long, hard hours all his life. He rarely took time off. In mid November 1891, he wrote to his son that he was suffering from a cold that was taking a little longer than usual to shake off. But in true Notman style, he continued to work despite his illness. By November 20th, the cold had settled into his lungs and he had finally taken to his bed to rest. On November 25th, 1891, William Notman passed away from pneumonia. He was 65 years old. William McFarlane took over the business and brought his youngest brother Charles on as a full partner. When William McFarlane passed away in Vancouver in 1913, Charles ran the studio until 1935, when he sold the business to the Associated Screen News. In 1957, McGill University acquired the Notman Collection which included 400,000 photographs, 43 Index books, assorted picture books and family memorabilia such as letters, postcards and other items. The collection is now in the care of the McCord Museum of Canadian History.

William Notman, a pioneer of Canadian photography, left Canada a legacy of images that show a nation in transition. He has given us a living record of who we were as a growing nation and gave us glimpses of who we would become. If you would like to search through the many images that William Notman and Son Studios produced, please go to the McCord Museum website. All the Notman images shown here are courtesy of the McCord Museum’s Notman Collection. A special thank you goes to the McCord Museum for making the story and images of William Notman accessible to all Canadians.

Welcome back Laura, missed your history lessons!!! A great story of William Notman’s rise to fame. Looking forward to many more fascinating stories in the future. Keep up the good work!!

Thanks, June! Happy to be back and writing again. Let’s hope this year is not quite as insanely busy!

Laura