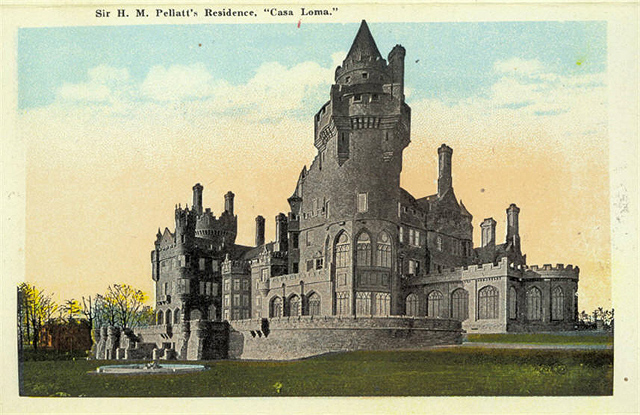

Canadian Castles Part V: Casa Loma, Toronto

We have come to the final chapter of our series on Canadian Castles and we end with the youngest of them all, Toronto’s Casa Loma. Since its construction, Casa Loma has been a tourist attraction and prominent landmark in the city of Toronto. It was built as a dream castle for wealthy financier and military man Sir Henry Pellatt and his wife, Lady Mary Pellatt. When construction began on the castle in 1911, Pellatt had amassed a vast fortune by investing in a number of Canadian businesses which included the Toronto Electric Light Company, the Home Bank of Canada and Cobalt Lake Mining. At the height of his financial success, Pellatt was the Chairman of 21 companies and through his own personal investments, he was in control of 25% of the Canadian economy. But before he even moved into his “dream home on the hill”, the seeds for his downfall were being sewn. Unlike his fellow Canadian Castle owners, Pellatt was forced to vacate his property less than a decade after he moved in.

Major-General Sir Henry Mill Pellatt was born January 6, 1859 in Kingston, Ontario. In 1861, his family moved to Toronto where Pellatt would remain for the rest of his life. His Scottish born father, Henry Sr., developed a successful stock brokerage in Toronto and found great success there as a financial advisor and investor. Since childhood, Sir Henry had been an avid military enthusiast and it appeared to his family that a life in the military was in his future. In 1876, Pellatt enlisted as a rifleman with the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada and attended Upper Canada College in Toronto. Upon leaving UCC, Pellatt became a clerk in his father’s brokerage where he would eventually rise up and become a full partner in the firm by 1883. Over those years in working with his father, Pellatt learned the ins and outs of financial investing and securing business deals on all levels. He also decided in this time that, although he loved his involvement with the Queen’s Own Rifles, he knew it would not make him a rich man, so he decided to remain on as their benefactor while continuing to seek his fortunes through investments. Pellatt was involved in business at the right time in the nineteenth century to take advantage of two major technological advances: the railways and hydro-electric power.

Pellatt was still a young man in 1883 at the age 24 when he became owner of the Toronto Electric Light Company which had been founded by J. J. Wright in 1881. This company would be responsible for bringing most of the electric street lights to Toronto. Previous to 1881, street lighting was kerosene based and this meant an extensive program was put in place to remove all the kerosene lamps and posts to replace them with electrical posts and wiring. Pellatt also became involved in the building of several hydro electric power plants in the Niagara region which would supply power to southern Ontario. When his father retired from the brokerage in 1892 leaving him in charge, Pellatt became more aggressive in his business dealings and invested in a number of projects he deemed to have a bright and successful future. His nickname in the 1880s and 1890s was “The Plunger” because Pellatt seemed to have a knack for diving head first into all his business dealings and clearly he made sound choices for all those businesses did well and brought him very profitable returns. By the turn of the twentieth century, that golden touch Pellatt possessed saw him at the head of over 20 companies, he was investing in ventures like the Canadian Pacific Railroad and the North West Land Company and he was in control of one quarter of the Canadian economy, a staggering feat which has never been repeated by a single individual since. But, the highlight of Pellatt’s power and recognition came in 1905 when he was knighted by King Edward V for his duties to Queen Victoria in his role as commanding officer and chief benefactor of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada and for bringing hydro-electric power to hundreds of thousands of southern Ontarians. Now, one of the richest men in North America, Pellatt began to draw some simple designs that would later become his dream home and one of Toronto’s best known landmarks of architectural design.

Much like BC coal baron Robert Dunsmuir had promised to build his wife Joan a castle for coming to Canada, Pellatt also promised his wife, Mary, a sprawling castle. Mary Pellatt was a force in Toronto society in her own right. She was known for throwing lavish dinner parties that everyone on Toronto’s society list wanted invitations to. Mary also became the first Chief Commissioner of the Girl Guides of Canada in 1912 and remained in that post until ill-health forced her to resign in 1921. Pellatt showed Mary the 25 acres of land he bought a few years before which sat on the Davenport Hill escarpment at the north end of Spadina Road. After toying with a few names for his wife’s castle, like Maryhill Castle, Pellatt settled on the name Casa Loma, which is Spanish for “House on the Hill”. He had a location picked out and a few simple drawings to go on so the next logical step was to hire an architect to put the paper dreams into brick and mortar reality.

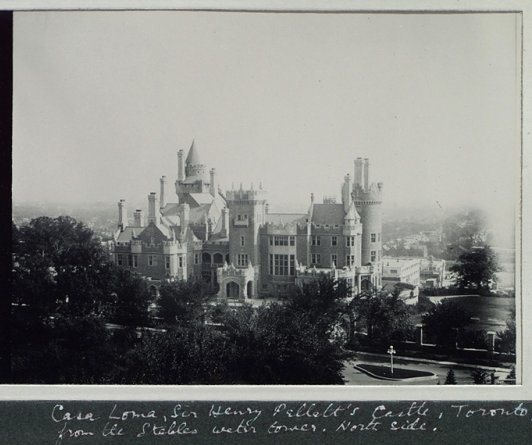

The architect chosen for the job was Edward James (E. J.) Lennox. Lennox was a dominant force in Toronto architecture in the early part of the twentieth century. Among some of his most noted works are the Old City Hall, the Bank of Toronto on Yonge and Queen Streets, The Athletic Club building and the King Edward Hotel. In an upcoming history series on noted Canadian architects, I will profile E. J. Lennox and his contributions to the Toronto built heritage landscape in further detail. For the Casa Loma project, Lennox incorporated the Gothic Revival and Richardson Romanesque architectural styles. Pellatt had made many sketches of castles and baronial homes during his frequent visits to Europe and he said that some of his inspiration for Casa Loma came from England’s Windsor Castle. Construction began in 1906 on the stables and Hunting Lodge. Once these two buildings were completed in 1911, the Pellatts moved into the Hunting Lodge while construction on the main castle began. No expense was spared in building Casa Loma. It cost Pellatt over $5,000,000 to construct and furnish his dream castle and in today’s currency, that is equivalent to almost $65,000,000. The castle itself boasted the most modern technologies available. The castle was equipped with electric power, it was the first private residence in Toronto to be equipped with an elevator as Mary Pellatt quite often needed a wheelchair to get about, and there was an entire telephone exchange to the castle grounds which accommodated 59 phones. It has been said that on some days, the switchboard operator at Casa Loma was busier than the switchboard operator for the entire city of Toronto! In addition to these new fangled things, the castle had 98 rooms, 30 full bathrooms, 25 large fire places, a 60 foot long indoor swimming pool (though uncompleted), a conservatory that housed exotic and rare tropical plants, a wine cellar that could hold 1,700 bottles, three bowling alleys to entertain guests and an indoor 160 foot long shooting range. Construction was completed by 1914 and the Pellatts moved in to begin furnishing their dream home. Antiquities from Europe were acquired to furnish the home including a grand pipe organ that cost $75,000. Over 40 domestic and grounds workers were hired and many of them lived in the Hunting Lodge in their off hours. Although the Pellatt’s entertained lavishly in public, behind the scenes it was a slightly different story. The beginning of the Great War in 1914 would cause Canada to go into debt and many businesses pulled in their purse strings in order to weather the economic storm. This tightening of capital meant that investments for Pellatt began to increasingly sour as the War continued. The introduction of the “temporary” income tax for all Canadians also began to eat into many incomes, including those of the wealthy. Pellatt assumed this would be a temporary glitch in his overall financial portfolio and that things would eventually improve. Unfortunately, for Pellatt, they did not.

By the end of the Great War in 1919, Canada was thrust into a major economic depression that was almost as bad as the Great Depression of the 1930s. Businesses were forced to close, veterans returning from the trenches of Europe had difficulty securing work, and the temporary income tax was here to stay which meant further belt tightening from many Canadian families already financial stretched. Pellatt was also the victim of a few government deals that saw his control over a few companies vanish. The Ontario Government formed the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario in 1906 and subsequently privatised power in the province. This forced Pellatt from his control of the Toronto Electric Light Company and he received no financial compensation from the Government for this. Also, one of the 21 companies he controlled was an aircraft manufacturing plant. Again, due to the Canadian war effort of 1914-1918, the Government took over control of this plant without compensating Pellatt. He then decided to turn his attention to land speculation and real estate in both Toronto and the western Canadian provinces. But even Pellatt couldn’t predict how sour the economy would go by 1919 and he lost money in these ventures as well. However, Pellatt’s largest financial loss came when the Home Bank of Canada, an institution he co-owned, failed in 1923. The Bank failed because of some shady and very questionable loaning practices including fraudulent land deals in Quebec and the buying of phantom timber rights in British Columbia. In the end, the Royal Commission led by Prime Minister Mackenzie King investigating the Home Bank saw 10 of the Bank’s Board members and Directors brought up on fraud charges, one Director committed suicide to avoid arrest, while over 600,000 prairie farmers and a large portion of Toronto’s catholic community lost their entire life savings. Pellatt also lost much of his investments in the bank, worth just under $2,000,000. Not only was Pellatt seeing the disintegration of his investments, he was also faced with mounting medical costs for his wife, Mary. The upkeep of Casa Loma was also becoming a financial burden by the early 1920’s. Maintenance alone was costing $100,000 a year, wages were estimated to be $25,000 a year, heating with coal cost just over $15,000 a year and his property taxes were estimated at about $12,000 a year. And, like a number of people across Canada in the early years of income tax, he wasn’t being completely forthright with what he was earning and this oversight eventually caught up with him.

When the Home Bank of Canada collapsed in 1923, creditors came knocking on Casa Loma’s door and the one leading the pack was the City of Toronto. Initially the City couldn’t seize the castle because Pellatt had put it into his wife’s name and it was Pellatt himself who was in financial trouble, not Mary technically. However, the City decided to seize the assets of the house in 1924 which meant all the furnishings and moveable chattel was to be sold in a public auction to recover their back taxes owed. What initially coast Pellatt $1,500,000 to furnish Casa Loma was sold at rock-bottom prices where only about $200,000 was made. Jacobean chairs, dating to the reign of King James I (1603-1625) were sold for $30 each. The Grand Pipe Organ, purchased for $75,000 sold for $40, and Lady Mary’s British Regency Period (1795-1837) bedroom set sold for just $45. The sale of these items inevitably forced the Pellatts out of Casa Loma and they retreated to a small farm in King City. Here, Lady Mary died of heart failure a few months later, no doubt the stress of their situation had accelerated her already declining health. With the death of Lady Mary, Pellatt was able to get the castle back as a bequeath in his wife’s will. However, because he now officially owned the castle, the City of Toronto could legally seize it for the taxes he owed. Pellatt could not afford the $27,000 owed as he was virtually penniless, so he had no choice but to hand over the castle to the City. The dream that began less than a decade before for the Pellatts was now officially over.

Casa Loma ended up going through a couple reincarnations before it became a museum in 1937. First, a syndicated group from New York leased the site and turned it into a luxurious hotel in 1927. Beautifully decorated suites sold for hundreds of dollars a night to the world’s financial elite who came to Toronto on business. There was also a successful nightclub on the ground floor of the castle that attracted a wide range of patrons. These two ventures were to be short lived, however, as the stock market crash of 1929 threw North America into another financial crisis with this one much worse than the post Great War recession. Casa Loma then sat unused, unheated, and suffered severe vandalism until the City decided what to do with it. A petition began to circulate that local residents wanted the building demolished because it had become an eyesore with its boarded up windows and vandalised exterior. Then, in 1937, the Kiwanis Club came to the castle’s rescue. The Kiwanis Club of West Toronto approached the City about taking the building over, fixing it up and turning it into a tourist attraction. The City agreed and after an extensive revitalisation and restoration period, Casa Loma was opened to visitors and has gained in popularity ever since. Casa Loma is one of the City of Toronto’s most popular tourist destinations (second only to the CN Tower) and is a major venue for weddings, films, conferences, and lecture series.

So what happened to Sir Henry Pellatt? Pellatt made one last visit to his beloved castle in 1938 to see the work the Kiwanis Club was doing to turn Casa Loma into a grand destination once again. Pellatt was said to have been impressed by the work and happy this piece architectural history would continue to be a part of the Toronto landscape. As for Pellatt himself, any investments he had left faded with the stock market crash of 1929 and he was left virtually destitute. His former chauffeur, who lived in a modest bungalow on Toronto’s Queen’s Avenue, took his former employer in when he had nowhere else to go. Pellatt died on March 8, 1939, still owing about $6,000 but only had his clothing and $200 left to his name. Whether it was capitalist greed, ill-advised investments, or just plain bad luck and bad timing, it was a tragic end to such a dominant figure in Toronto’s late Victorian and early Edwardian history.

Today Casa Loma is a must see destination for anyone visiting the Toronto area. Every season there is something new to experience and enjoy from very elegant afternoon teas in the garden, Halloween and Christmas parties for children, lectures on sustainable vegetable and flower gardening, Medieval re-enactments, Sunday brunches, and countless activities for families throughout the year. The Kiwanis Club still maintains Casa Loma and all the proceeds raised through admissions and activities go to supporting a number of charities that the Club supports in the Toronto area including a number of children’s initiatives. For more information on admissions and activities, please check out the Casa Loma Museum Website. My thanks to the Casa Loma Museum and the Kiwanis Club of West Toronto.

Fascinating but sad history for such a beautiful building. Great article, Laura!

Yes, it is a sad story isn’t it? To be so high then to come crashing down so hard like that. No matter the reason for it, it is a sad story. Thanks for reading, June!

Agreed. Such a sad story. But he must have been a good man otherwise his chauffeur wouldn’t have take him in.

Yes, I think so too. I think he was just an unfortunate victim of bad timing when it came to the markets.

Thanks for reading, Kayla!

Laura

[...] great series by Laura at History to the People concluded this week with a post on Casa Loma in Toronto. I’ve been there several times but this in depth post on the owner Sir Henry Mill Pellatt [...]

Wow, very sad story. Did he not have family that could have supported him? They may not have had the money to pay the debts but at least for moral support?

Very good story. Thanks.

Mark

Hi Mark,

I didn’t look into this too deeply but the Pellatts did have an only child, a son named Reginald born in 1885. He married Marjorie Carlyle Perry on Oct 14, 1908 in Toronto. I couldn’t find any references to children from that marriage. Reginald had a career as a stock broker and also served as the CO of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, just like his father had. Reginald died on July 28, 1967 and is buried at Toronto’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery. When Henry died, his body lay in wake at Reginald’s home on Walmer Rd in Toronto for three days. Henry also had a number of neices and nephews by his brothers and sisters and many of those descendants are still active with the upkeep of Casa Loma. So in terms of why exactly Henry went to live with his former chauffeur and not with Reginald or another family member is a mystery to me at this point. Perhaps it was a sense of pride? I don’t know. But it is an interesting question, isn’t it?

Say hello to Devon for me….it looks gorgeous in the snow! Take care.

Laurie